https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/guineaworm/prevent.html

How does Guinea worm disease spread?

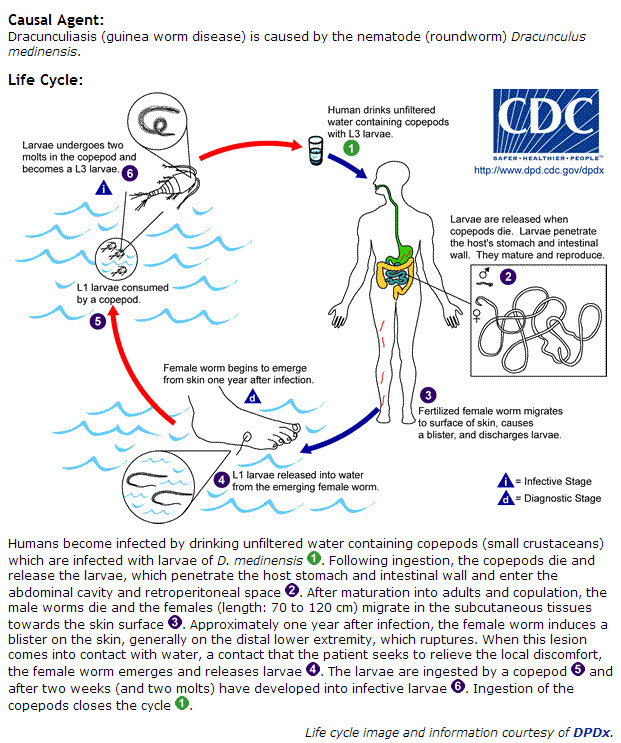

People become infected with Guinea worms by drinking unfiltered water from ponds and other stagnant water containing copepods (tiny “water fleas” too small to be clearly seen without a magnifying glass). These copepods swallow Guinea worm larvae. People who drink water containing copepods that have swallowed Guinea worm larvae can develop Guinea worm disease.

Alternatively, it is believed that people and animals might also become infected by eating certain aquatic animals, like fish or frogs, that might have swallowed infected copepods and might carry Guinea worm larvae but do not themselves suffer the effects of infection. If the fish or frogs are eaten raw or undercooked, the Guinea worm larvae are then released into the human or animal digestive tract.

Following ingestion, the copepods die and release the larvae, which penetrate the host stomach and intestinal wall and move to the connective tissues of the abdomen where they mate. During the next 10–14 months, the male worm dies and the pregnant female worm grows to 60–100 centimeters (2–3 feet) in length and as wide as a cooked spaghetti noodle.

When the adult female worm is ready to release her larvae, approximately 1 year after infection, she moves to a spot just beneath the skin. A blister then forms on the skin where the worm will eventually emerge. This blister may form anywhere on the body, but usually forms on the legs and feet. This blister causes a very painful burning feeling and it bursts within 24–72 hours.

Whether to relieve pain or as part of their daily lives (e.g., to collect water, bathe, wash clothes, cool off, etc.), people and animals infected with Guinea worm usually enter bodies of water. Water contact triggers the Guinea worm to release a milky white liquid that contains millions of immature larvae into the water. Copepods swallow these larvae and the cycle begins again.

What are the signs and symptoms of Guinea worm disease?

People do not usually have symptoms until about one year after they become infected. A few days to hours before the worm comes out of the skin, the person may develop a fever, swelling, and pain in the area. More than 90% of worms come out of the legs and feet, but worms can appear on other body parts, too.

People in remote rural communities who have Guinea worm disease often do not have access to health care. When the adult female worm comes out of the skin, it can be very painful, take time to remove, and be disabling. Often, the wound caused by the emerging worm develops a secondary bacterial infection. This makes the pain worse and can increase the time an infected person is unable to function from weeks to months. Sometimes, permanent damage occurs if a joint is infected and becomes locked.

What is the treatment for Guinea worm disease?

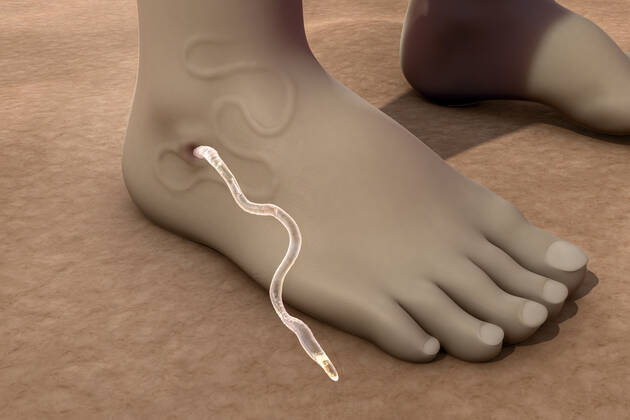

There is no drug to treat Guinea worm disease and no vaccine to prevent infection. Once part of the worm begins to come out of the wound, the rest of the worm can only be pulled out a few centimeters each day by winding it around a piece of gauze or a small stick. Sometimes the whole worm can be pulled out within a few days, but the process usually takes weeks. Care must be taken not to break the worm during removal. If part of the worm is not removed, there is a risk for secondary bacterial infections and resulting complications. Anti-inflammatory medicine can help reduce pain and swelling. Antibiotic ointment can help prevent infections.

Where is Guinea worm disease found?

Only 28 cases of Guinea worm disease were reported in humans in 2018. These cases were reported in Angola (1 case), Chad (17 cases), and South Sudan (10 cases). As of February 2018, the World Health Organization had certifiedexternal iconexternal icon 199 countries, territories, and areas as being free of GWD transmission. Animals infected with D. medinensis, mostly domesticated dogs, have been reported since 2012. Most animal infections have occurred in Chad but some have been reported in Ethiopia and Mali. In 2018, Chad reported 1,040 infected dogs and 25 cats; Ethiopia reported 11 infected dogs, five cats, and one baboon; and Mali reported 18 infected dogs and two cats.

Who is at risk for infection?

Anyone who drinks from a pond or other stagnant water source contaminated with Guinea worm larvae is at risk for infection. Larvae are immature forms of the Guinea worm. People who live in countries where GWD is occurring (such as Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan) and consume raw or undercooked aquatic animals (such as small whole fish that have not been gutted, other fish, and frogs) may also be at risk for GWD. People who live in villages where there has been a case of GWD in a human or animal in the recent past are at greatest risk.

Is Guinea worm disease a serious illness?

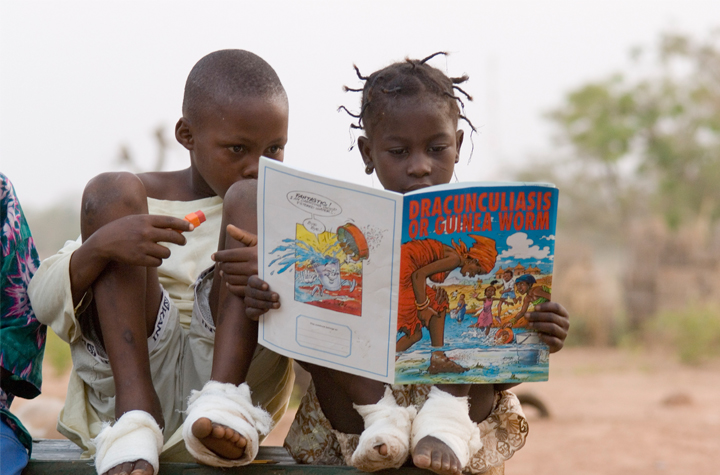

Yes. The disease causes preventable suffering for infected people and is an economic and social burden for affected communities. Adult female worms come out of the skin slowly and cause great pain and disability. Adults with active GWD might not be able to work in their fields or tend their animals. This can lead to food insecurity and financial problems for the entire family. Children may be required to work the fields or tend animals in place of their sick parents or guardians. This can keep them from attending school. Children who have GWD themselves may also be unable to attend school. Therefore, GWD is both a disease of poverty and a cause of poverty because of the disability it causes.

How can Guinea worm disease be prevented?

Teaching people to follow these simple control measures can prevent the spread of the disease:

- Drink only water from protected sources (such as from boreholes or protected hand-dug wells) that are free from contamination.

- If this is not possible, always filter drinking water from unsafe sources using a special Guinea worm cloth filter or a Guinea worm pipe filter to remove the copepods (tiny “water fleas” too small to be clearly seen without a magnifying glass) that carry the Guinea worm larvae. Unsafe water sources include stagnant water ponds, pools in drying riverbeds, and shallow hand-dug wells without surrounding protective walls.

- Cook fish and other aquatic animals (e.g., frogs) well before eating them. Bury or burn fish entrails left over from fish processing to prevent dogs from eating them. Avoid feeding fish entrails to dogs. Avoid feeding raw or undercooked fish or aquatic animals to dogs.

- Prevent people with blisters, swellings, wounds, and visible worms emerging from their skin from entering ponds and other water sources.

- Tether dogs that have blisters, swellings, wounds, and visible worms emerging from their skin to prevent the dogs from entering ponds and other water sources.

In addition to these health education measures, the Guinea Worm Eradication Program (GWEP) also undertakes the following two additional water-related measures to prevent GWD:

- GWEP staff treat targeted unsafe drinking water sources at risk for contamination with Guinea worm larvae with the approved chemical temephos (ABATE®*) to kill the copepods and reduce the risk of GWD transmission from that water source.

- GWEP staff provide targeted communities at risk for GWD with new safe sources of drinking water and repair broken safe water sources (e.g., hand-pumps) if possible.